Radial and ulnar fractures are common in small dogs, and they often affect the distal backbone. Traumatic radial and ulnar fractures usually occur in the middle of the backbone, but may also occur anywhere. Open traumatic fractures may occur due to limited coverage of soft tissue from the middle to distal radius.

Initial diagnosis

animals with backbone fractures of the radius and ulnar were observed for the first time, and the appearance was very unstable; due to the small soft tissue coverage, the bone friction sound was obvious during exercise. In order to determine the best treatment options, it is important to accurately determine the symptoms and history.

age

animals with undeveloped bones have good healing ability, and most dogs under 6 months of age have healing time of 6 to 12 weeks when their limbs are stable enough. However, if there is dislocation, misalignment and growth plate damage, then the limb horn deformity will occur as the animal continues to grow. The healing speed of kittens and puppies under 10 weeks old is amazing. Callus can form within 10 days, so if surgical intervention is planned, no delay should be delayed.

Animals with mature bones take 2 to 5 months to heal, which will affect how to achieve rigid fixation of the fracture, because 5-month external fixation or external osteotomy requires multiple reexaminations, sedatives, bandage replacement, frame cleaning, etc.

Breed

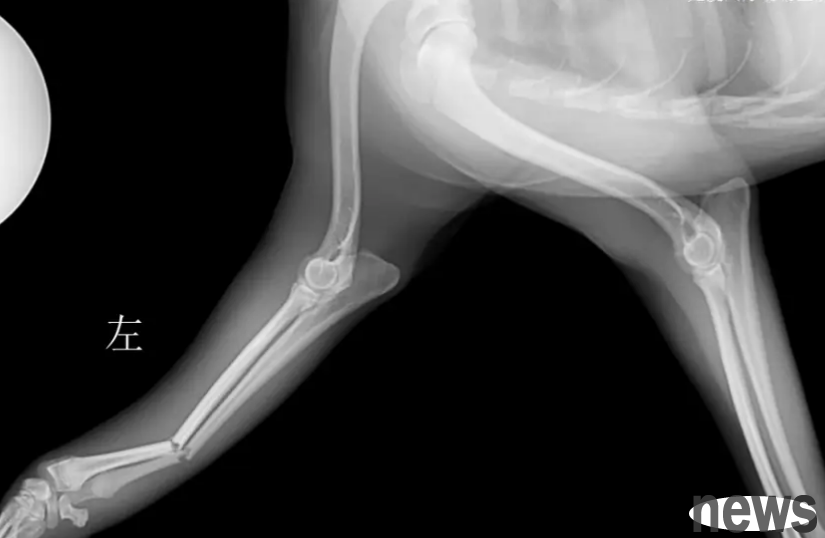

toy dogs are prone to distal radial-ulnar fractures. Unfortunately, the non-union rate of fractures in the radius and ulnar bones of toy dogs is high (80% or higher), especially when treated with external osteotomy (Fig. 1). The low healing rate is caused by a variety of factors, but it is mainly believed to be due to the reduced blood vessel density and reduced blood vessel branches in the distal radius of toy dogs. This means that these fractures will not be able to form bone healing without rigid fixation of the fracture (usually with steel plates and screws).

A toy Poodle hybrid dog after 8 weeks of external bone jointing with splints, the radial and ulna healing delayed/unnecessary connection of head and tail and mid-lateral X-rays. The photo is from the author of this article.

Species

The most important thing is to remember that cats are not small dogs, their anatomy and function are very different, so cats must be treated specifically in cases of radial and ulnar fractures.

One of the most obvious differences between cats and dogs is that cats' paws are more likely to be respin, which requires a certain degree of mobility between the radius and ulnar. This level of mobility between the bones means that traumatic fractures in cats are more likely to affect the ulna or radius alone than dogs. This also means that the radius and ulna cannot be fixed internally to each other like a dog, so each bone needs to be fixed hard when it is broken.

Cats may have cat patella & dental syndrome (PADS), which may cause non-traumatic fractures of the moustache. Therefore, it should be assessed whether there is a concurrent presence of non-traumatic fractures and deciduous teeth retention.

Determine treatment options

It is easy for people to focus on the shaking fractured legs and believe that immediate measures should be taken to address it. While the next reasonable move seems to be surgery, it is best to stop and consider whether there may be other injuries that require treatment before the fracture is finally treated.

Concurrent lesions

Traumatic radial and ulnar fractures caused by blunt trauma (such as being hit by a car or falling from a high place) may usually be accompanied by complications. Animals should be evaluated for chest, abdomen, and nervous system damage.

Comprehensive and thorough clinical examination can help evaluate the presence of rib fractures, pneumothorax, abdominal wall hernia and whether the animal is in shock.

A comprehensive neurological examination should be conducted, focusing on the removal of head injuries, cervical fractures and arm nerve plexus injuries.

Horner's syndrome, loss of dermatitis or pupil shrinkage may indicate a pleural plexus injury, and further examination should be performed if these symptoms are present. Because the radial nerve has the function of innervating the triceps and the radial extensor of the carp, the radial nerve is crucial for weight bearing in the forelimbs of the dog.

For many dogs with forearm fractures, it is difficult to perform retraction and spinal reflexes due to pain. Therefore, evaluating whether the radial nerve is severely damaged can be accomplished by evaluating the superficial sensation of the dorsal dorsal innervation of the radial nerve.

While covering the animal's eyes, take small hemostatic forceps and gently pinch the skin on the back of the affected leg claw. If the animal tries to keep her legs away from you and/or sends a signal to stop pinching their paws, the test is positive. This suggests a superficial sensation of the claw back, and in most cases where the radial nerve function can be fully restored within 6 weeks.

The lack of superficial feeling should be carried out in a timely and detailed neurological examination to determine the severity of the injury and the prognosis of functional recovery. But be aware that some dogs who are in shock after trauma or after taking a lot of opioids may show false negatives in this test.

Thoracic, abdominal X-rays and ultrasound examinations, and electrocardiograms can be used to evaluate rib fractures, pneumothorax and hemothorax, diaphragmatic hernia, myocardial injury (arrhythmia), abdominal wall hernia, urinary tract rupture and abdominal bleeding.

Comprehensive orthopedic examination helps to assess the presence of any concurrent fractures; however, non-traumatic fractures in cats may require X-rays because the lack of associated soft tissue swelling makes it more difficult to detect. Falling from high places is often accompanied by ligament injury, so special attention should be paid to assessing ligament support in the wrist and tarsal joints of these animals.

When checking for concurrent injuries, a temporary soft padded bandage ± splint may be required to place a fractured forearm to help the animal stay comfortable and prevent further contamination of the wound. X-rays of fractures

crani-caudal and mid-lateral lateral films, including the elbow and carpal bones, are usually sufficient to diagnose most radial and ulnar fractures. For highly comminuted fractures, oblique filming or computed tomography may help further evaluate the presence of clefts that may affect the treatment regimen, especially when the cleft is close to the forearm wrist joint. Direct image views are usually easier to obtain without bandages, but if there are wounds, you should use dressings and light bandages to prevent contamination.

Splitter, cast or surgery?

When deciding the final treatment plan, the biomechanics, mechanic principles and various clinical factors of the fracture should be considered, including animal personality and client budget. A detailed description of the treatment regimen and its risks and benefits is beyond the scope of this article, but the following three points are worth noting: Any toy dog with radial and ulnar fractures should undergo surgical fixation, usually rigid internal fixation, and should not be treated with cast or splint. With the increasing popularity of toy poodle hybrids, this should also be extended to any breed with "toy dog characteristics" forearm bones, such as mini-Labradors, Pomskies (a mixed race of Siberian Husky and Pomeranian), Italian Greyhound hybrids, etc. It is important to consider the size of the implant used for these dogs, as too large implants can lead to osteoporosis.

2

Young animals are at risk of limb keratinization after radial and ulnar fractures. The situation may be worse if excessively long screws are used at the proximal end of the radius and a bone joint is formed.

Similarly, if the limb is poor, a bone connection will form between the radius and the ulna and produce a large number of callus, which is most common in external junctions.

Although young animals with fractured bones can recover quickly, surgical fixation is recommended to minimize the risk of bone joints (remember that the proximal screws should be short), rather than fixing the legs with splints or plasters. However, if young animals only have radial or ulnar fractures, the chance of bone joints will be greatly reduced and external junctions may be very successful.

3

cats are less able to accept forelimb splints or plaster (will "dump" them out before even getting home). There is also a great degree of mobility between the radius and ulnar, which is important to protect, but even if only one bone is affected, it will reduce the overall stability of the forearm fracture. Therefore, forearm fractures in most cats can be treated with surgical fixation.

However, the very young, healthy kitten has amazing healing ability; the author once had a six-week-old kitten, and since we had to prioritize some other fractures, we tried to splint it instead of surgery; after only two weeks, the fracture had completely healed, and the cat endured only one day of splint treatment.

A lateral X-ray after a baby cat (6 weeks old at the time of fracture) was found in a cage for 3 weeks and suffered from simple, mild dislocation, complete fracture in the middle section of the backbone of the radius and ulna. Both fractures have healed, no bone combination has been formed, and no keratinization has occurred.

Other tips

If young and healthy dogs only suffer from radial or ulnar fractures, small displacement, closed fractures, they can recover well by just 6 to 12 weeks of splint fixation. We tend to use gypsum bandages (Figure 3) to tailor the lateral splint for each case in order to stabilize the elbow joints (to effectively complete the splint/plaster fixation, the upper and lower joints must be stabilized). Using gypsum bandages can avoid the full set of gypsum, as we can tailor a sturdy, fitted ply for each animal, and use a gypsum saw to trim the edges, etc.